So, top of the list of the just released 2015 edition of the Fortune 500 companies are the usual suspects and industries: US based companies leading but China is steadily catching up. Chinese firms, back in 2012, overtook their Japanese peers on the Fortune Global 500 list of the world’s largest companies for the first time, and this dominance is likely to continue into the near future due to a number of factors – the younger demographic profile in China being the primary driver of consumer demand.

The Rise and Dominance of Chinese Newcomers

Ninety-eight (20%) of the companies on the list are based in China, including those headquartered in Hong Kong. That puts China second only to the United States, which has 128 companies (26%) on the list. In contrast, traditional European colonial powerhouses such as France, Germany and the United Kingdom came in with 31, 28 and 29 companies respectively. As has been cited in other places , China had just 10 companies appearing on the Fortune list in 2000 and 46 companies in 2010 compared with the United Sates which had 179 companies in 2000 and 139 American companies made the list in 2010.

Big but Weak?

At the core of the phenomenal rise of Chinese companies into the pantheon of global conglomerates are the country’s State-Owned-Enterprises (SOEs) backed by the central ethos of state-led capitalism both within China, and externally with investments into frontier markets in places like sub-Saharan Africa. The foray of many Asian SOEs into emerging markets has been catalysed by the demise of the bipolar world in the early 1990s, which brought with it the rise of liberal economic policies of deregulation, free trade, capital flows and globalization.

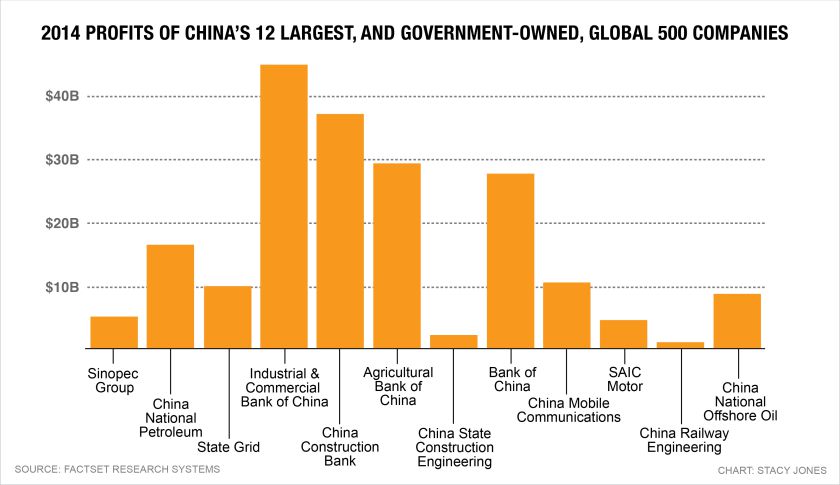

Over 75% of the Chinese companies on the list are all state-owned and includes massive banks such as the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China and China Construction Bank and oil companies such as Sinopec and China National Petroleum. Only 22 of the 98 Chinese companies on the list are private. Characterized by their asset-heavy operations and resource monopolies, the vast majority of Chinese companies on list represent traditional sectors: energy, telecommunications, finance and real estate.

Internationalisation Drive and Business Strategy Imperatives

Many of these companies have in the last couple of years, moved towards internationalisation and branding as part of their business strategy by leveraging their local monopolies to advance in key emerging markets particularly in natural resource abundant African countries. I would not be surprised to see more emerging Chinese consumer brands increasingly overtake western ones as Asia and other emerging markets continue to grow fuelled by a new middle-class boom. Do not blink in suspense when you see a lot more FAWs, Geelys, Dongfengs or SAIC Motors’ brand on the road compared to a Ford or Volkswagen.

Why? Because as is argued “These companies have are selling ‘good enough’ products at low prices to middle-class Chinese consumers,”…After studying (and, increasingly, buying) Western competitors and exploiting Chinese manufacturing efficiencies, they are now poised for global market gains.” They have built comparative and competitive advantages that allow them to produce at an efficient frontier with minimal costs.

Lessons: African Enterprises and the Developmental State

Africa today is at a great turning point buoyed by the increased integration of the economies of the 54 countries that make up the union into the global economic order. As the Chinese and other South East Asian countries have shown, we need to actively promote innovative industrial transformation to improve quality and efficiency if we ever are to become competitive on an international scale. Leading African enterprises such as the Dangote Group and other MSMEs, with the support of their respective governments, much as the Koreans and Chinese have shown, should grasp the opportunity to restructure their respective industries and actively participate in a strategic international rollout. Not only should they achieve success in terms of business turnover, but they could also truly become global brands and leaders through the nexus of a healthy industrial ecology supported by an active and well-educated labour force.

The institutional structure of the businesses system in places like China and South Korea is such that the State has woven itself into the very fabric of the economy — e.g. in the financial system through ownership of banks that allowed direct influence over the allocation of capital, corporate governance, and even in social capital formation. Within the literature, the goal of South Korea’s development policies (an offshoot of the post-war Japanese model) was centred on economic growth as a policy priority. For example, the overarching vision “was to develop the country by using administrative means to accelerate the progress of South Korean industries from labour-intensive to capital-intensive, and ultimately to technology-intensive industries …through and subsidized access to finance, capital controls, inward foreign direct investments, requirements to meet ever-increasing export quotas, etc. ”

Danger Ahead

However, this approach is not without its weaknesses and critics. First, the capital efficiency turnover of most State companies tends to be less than private ones due to a reduced incentive effect. That is, less innovation and big risky bets given the prospect of a government bailout ― i.e. moral hazard and the “too-big-to-fail syndrome”. This tends to stifle private sector growth and efficiency. As the Economist magazine argues: “When the government favours one lot of companies, the others suffer. In 2009 China Mobile and another state giant, China National Petroleum Corporation, made profits of $33 billion—more than China’s 500 most profitable private companies combined …In many countries the coddled state giants are pouring money into fancy towers at a time when entrepreneurs are struggling to raise capital”.

Second, despite the strides made in recent years, many African countries are still predatory, rent-seeking clientelist states evidenced by high levels of corruption that enables political and business leaders to enrich themselves at the expense of the general public and welfare. Therefore, one wonders the extent to which the economic fruits of any State-led model of development, if any, will trickle down to the populace without favouring well-connected insiders over innovative outsiders. This has the tendency of accentuating nepotism and cronyism, thereby further exacerbating inequality and eventually discontent of the populace. Examples abound from South Africa’s failed Black Economic Empowerment Programme to the divestiture of State-Owned Enterprises in Ghana.

So the debate remains: what should be the proper role of the state in resource-abundant emerging economies of Africa such as Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana, Tanzania, Angola, etc.? How do we balance the welfare, innovation and efficiency issues vis-à-vis economic liberalization, and what should be the critical role of the State in this process? Is the visible hand of state-led capitalism superior to Adam Smith’s free market in some instances? It is no coincidence that a lot of emerging economies – i.e. BRICS and some G20 nations— have either had state-led development periods or remain very much in the midst of that experiment, China notably of all.

More Reading

- http://www.economist.com/node/21543160

- http://business.time.com/2011/09/30/state-capitalism-vs-the-free-market-which-performs-better/

- http://blogs.reuters.com/ian-bremmer/2012/07/03/are-state-led-economies-better/

- http://www.cato.org/policy-report/januaryfebruary-2013/how-china-became-capitalist

- https://hbr.org/2007/09/the-battle-for-chinas-good-enough-market

- http://www.worldcrunch.com/world-affairs/africa-as-investor-goldmine-why-this-time-it-s-for-real/havas-horizon-study-investments-development-economics/c1s19370/

- http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/consumer_and_retail/winning_in_africas_consumer_market?

- http://presse.havasparis.com/etude-exclusive-havas-horizons-financer-la-croissance-africaine-en-2015-2020-quelle-perception-des-investisseurs-internationaux/

- http://www.worldcrunch.com/opinion-analysis/is-africa-039-s-economic-miracle-just-a-mirage-/african-economy-brics-development-growth-/world-affairs/stemming-over-population-in-sub-saharian-africa/c1s5917

- http://blog-imfdirect.imf.org/2015/08/03/the-african-century/