|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

- Introduction

Governance in Africa has evolved and gone are the days when men, clad in military uniform, would just pop out of nowhere to seize the national radio and television station to announce to the general populace that a military coup has taken place ― with the exception of the recent coup in Burkina Faso. In the process, one military or democratic government was deposed in favour of another, and this was the existential practice in many African in the three decades following independence up until the 1990s when democratic ideals begun to permeate the political space.

Today, a cursory look at Africa’s landscape indicates that some progress has been made in improving governance on the continent as a whole with the advent of pro-democracy movements that took foothold in the 1990s. Today, there are less dictators and one-party states and there is evidential expansion of the political space to include multi-party democracy whereby elections are commonplace and vibrant opposition parties exist in some countries. Consequentially, civil liberties and the participation of the people in the political process have increased but not without its own challenges — having regular elections is not the end in itself; it is, at best, only a means to the end objective of social and economic emancipation. The recent election of Muhammadu Buhari and political transition in Nigeria after almost 15 years of PDP rule in the post-Abacha era, as well as civil protests in Burkina Faso, which ousted the 27 year old dictatorial regime of Blaise Campaore bear testament to the rise of political consciousness of the citizenry. Additionally, there have been major improvements within the policy environment that have catalysed a turnaround of Africa’s economic performance.

Between 2003 and 2008, the continent enjoyed robust annual 6.5 percent growth in GDP and this consistently remained over 5 percent of GDP in the ensuing years until recent times where forecasts have been on the downside due to difficult global trading conditions ― commodities plummet, liquidity tightening and weak domestic buffers due to fiscal consolidation.[1] The African Development Bank reports that “domestic demand has continued to boost growth in many countries while external demand has remained mostly subdued because of flagging export markets, notably in advanced countries and to a lesser extent in emerging economies… on the supply side, many African countries have improved their investment climate and conditions for doing business, which enhance long-term growth prospects. Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Senegal and Togo are even in the top ten countries worldwide with the most reforms making it easier to do business.”[2]

However, despite the gains ushered in by the twin political and economic reforms embarked on by African countries since the early 1990s, the strive for participatory democracy and human-centred development is still a major impediment to deepening social equity. Whereas Africa’s population is growing, poverty is still rife in many parts of the continent; education and health standards are low compared to global benchmarks and there is a huge pressure on the teeming but unemployed youth to makes ends meet. This has serious political and national security implications.

- Mo Ibrahim, Economic Growth and Governance

It is against the backdrop of these challenges as well as opportunities that the Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) was established back in 2007 to provide a composite measure of governance on the content. The 2015 Mo Ibrahim Index reports that progress on improving governance in Sub-Saharan Africa is stalling at a regional level. According to the 2015 measure, governance, defined by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation as the provision of the political, social and economic public goods and services that every citizen has the right to expect from his or her state and that a state has the responsibility to deliver to its citizens, actually deteriorated in 21 of Africa’s 54 countries between 2011 and 2014. Continentally, only an abysmal 0.2 point raise was witnessed to 50.1 (out of 100.0), with considerable changes in performance during the last four years at all levels of the Index, both at country and at category level. The marginal improvement in overall governance at the continental level is underpinned by positive performances in only two categories: Human Development (+1.2) and Participation & Human Rights (+0.7) ― all assessed out of 100.0. Both Sustainable Economic Opportunity (-0.7) and Safety & Rule of Law (-0.3) have deteriorated. However, despite progress stalling at the composite regional level, governance is still improving in most of the large, open economies that are driving growth in the region albeit at a slow pace –Nigeria, South Africa, Angola and Cote D’Ivoire.

Twenty-one countries, including five of the top ten namely Mauritius, Cape Verde, Botswana, Seychelles and Ghana deteriorated in overall governance performance since 2011. Only six countries registered an improvement across each of the four categories of the IIAG: Côte d’Ivoire, Morocco, Rwanda, Senegal, Somalia and Zimbabwe. In addition, three of Africa’s largest economies – Ghana, Tanzania, and Cameroon – saw their scores deteriorate with an average decline of 0.9 points (out of a possible 100) but this was dwarfed by the gains posted by Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, and Ethiopia, which gained an average of 5.4 points in the same reporting timeframe. The index did show varying trends at the regional level. Southern Africa remains the best performing region, with an average score of 58.9, followed by West Africa (52.4), North Africa (51.2) and East Africa (44.3). Central Africa is the lowest ranking region with an average score of 40.9, and is the only region to have deteriorated since 2011 — of course this is understandable given the notoriety of the region for political instability and military coups.

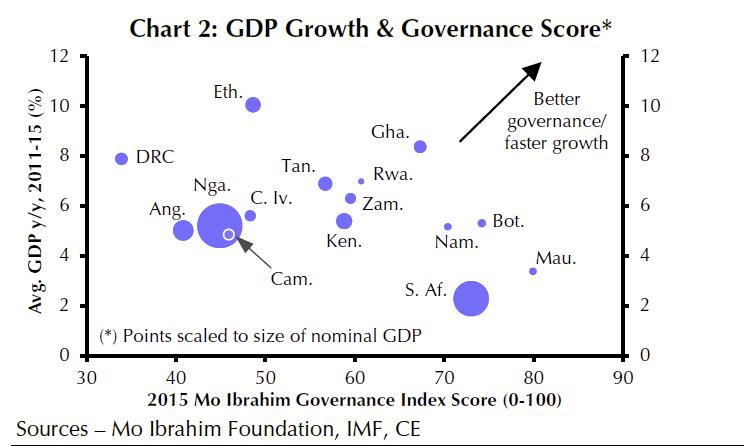

But to what extent is the index correlated to recent economic performance? Well the evidence is mixed. For example, a recent research report from another consultancy notes that Ghana is the only country to be both a high scorer on the Index (7 out 54 countries) and among the region’s fastest growing economies – partly due to a commodities boom, but so is mineral-rich DR Congo, which ranks 48 out of 54 countries on the Index. However, DR Congo grew faster at an average of 7.9% of GDP over the past four years than any of the top performers. This of course fails to take into account wealth distribution effects.

So, the top economies with better governance indices are much more likely to have a relatively better wealth distribution pyramid through the provision of public services and infrastructure despite growing at a smaller pace compared to the lower ranked countries. Reform of the state machinery will bring efficient bureaucracies and legislative clarity and form a critical pillar to attracting investment into manufacturing or service-oriented economies and even a greater role in commodity-driven economies if the resource curse is to be avoided. Commodity booms can take place in failed states as well as well-governed democracies but the difference between any two such countries in these categorizations will be the trickle-down effect of the wealth created via the institutional processes to check against abuse of power, fraud and corruption.

- Explaining the Methodology

The Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) is an annually published index that provides a statistical measure of governance performance in every African country. Governance is defined by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation as the provision of the political, social and economic public goods and services that every citizen has the right to expect from his or her state, and that a state has the responsibility to deliver to its citizens. This definition is focused on outputs and outcomes of policy. The IIAG governance framework comprises four categories: (1) Safety & Rule of Law – 25 indicators in four sub-categories; (2) Participation & Human Rights – 17 indicators in three sub-categories; (3) Sustainable Economic Opportunity – 29 indicators in four sub-categories; and (4) Human Development- 22 indicators in three sub-categories. These categories are made up of 14 sub-categories, consisting of 93 indicators. The 2015 IIAG is calculated using data from 33 independent, external data sources.[3]

- Concluding Thoughts

I agree with Mo Ibrahim, Chair of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, when he posits: “While Africans overall are certainly healthier and live in more democratic societies than 15 years ago, the 2015 Ibrahim Index of African Governance shows that recent progress in other key areas on the continent has either stalled or reversed, and that some key countries seem to be faltering. This is a warning sign for all of us. Only shared and sustained improvements across all areas of governance will deliver the future that Africans deserve and demand.”

In essence, in order not to erode the socioeconomic gains made in recent years, African governments must understand that the commitment to real grassroots democratic ideals, which have participatory democracy (not just elections) and the building of institutions at its core, is the only sure way to ensure fair and equitable development of the continent. I am often reminded by Barack Obama’s statement[4] to a packed house in Accra, Ghana on his inaugural sub-Saharan Africa trip as US President that “Africa doesn’t need strongmen, it needs strong institutions …no person wants to live in a society where the rule of law gives way to the rule of brutality and bribery. That is not democracy, that is tyranny.”

Africa, a very diverse and complex continent, is on the move and it sure is rising. Gone are the days when the old stereotypes of disease, war, famine and hopelessness were the norm. Instead, this common mantra has been replaced with one of a continent of hope; of rising and successful entrepreneurial stories evidenced by some of the fastest growing economies in the world. The only way to sustain the gains made over the past two decades is to ensure that true freedom and justice pertains ― a fair political system and ethical leadership, respect for individual rights and independent courts as well as the renewed commitment to economic and structural reforms to unleash the energies of the populace.

Download 2015 Mo Ibrahim Index Poster: http://static.moibrahimfoundation.org/u/2015/10/02193257/2015-IIAG-Poster.pdf

Further Reading:

[1] http://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/publication/africas-pulse-an-analysis-issues-shaping-africas-economic-future-october-2015

[2] http://www.africaneconomicoutlook.org/fileadmin/uploads/aeo/2015/PDF_Chapters/Overview_AEO2015_EN-web.pdf

[3] http://www.moibrahimfoundation.org/iiag/methodology/

[4] https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-ghanaian-parliament