|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

1. Introduction

On 17 August 2016, my attention was drawn to a news article published in the Daily Graphic, which inter alia, mentioned a group known as The Homeland Study Group Foundation (HSGF) based in Ho in the Volta Region of Ghana “agitating for the restoration of so called Western Togoland as a state to declare independence for Western Togoland on 9 May 2017.”[1] According to the leader of the group, “…. the Western Togoland were plebiscite citizens in Ghana and not until a declaration was made on 9 May 2017, the people will remain an appendix to the former Gold Coast (now Ghana). They also claimed that “…world historical documents had revealed that Western Togoland was a state and not a territory of Ghana.”

Fundamentally, HSGF claims that although residents of the Western Togoland voted in 1956 to become a union with the Gold Coast (now Ghana), the union has not been formally established by way of a unionized constitution to date.[2] That is, Queen Elisabeth II did not incorporate Western (British) Togoland in the Act establishing the Gold Coast (now Ghana). Thus, they are right in calling for a secession to form a new sovereign state.

However, do these arguments really stack up against the historical record? The purpose of this article is to analyse the recent calls by the HSGF in light of the existing historical narrative to address the following: (1) the history of Western Togoland (2) political associations in the Togoland (Unificationists vs Unionists) and (3) the plebiscite and matters arising.

2. History and Makeup of Western Togoland

Africa’s international boundaries were delimited and subsequently demarcated by European States following the 1884 Berlin Conference (Prescott, 1963; p1). The division of the former German colonies of Togoland, Kamerun (now Cameroun) and Tanganyika (Great Lakes Region) into British, French and Belgian Mandates after World War I was one of the most important boundary changes that took place.[3]

Prescott (1963) notes that before the European intervention “the Ewes were politically divided into about 120 subtribes lying between the centralised military kingdoms of Abomey and Ashanti. During periods of war temporary alliances were formed amongst the Ewe groups, but these were dissolved in times of peace.”[4] The Anglo-German boundary, which lay between Lomé and the Volta River divided Eweland into two protectorates namely British Gold Coast Colony and German Togoland. The British administered their mandate as an integral part of the Gold Coast Colony whereas the French kept theirs administratively separate from Dahomey (Benin) and Upper Volta (Burkina Faso). Both Togoland under the British protectorate and Togoland under the French protectorate were under supervision of the Trusteeship Council of the League of Nations (now the United Nations).[5] The Ewe area in the British controlled territory was formally constituted into the Trans-Volta-Togoland region in 1952 to enable effective administration as a single group (Prescott, 1963; p5). The landmass of British Togoland stretches from Bawku East district in the Upper East region and borders the Volta River up to the Gulf of Guinea.

Bening (1983) notes that the original boundary between the British colony of the Gold Coast and protectorate of Togo included not only the Ewe of the Keta and Peki districts in territory but it also divided the Mamprusi, Dagomba and Gonja states as well. The division of Togoland exacerbated the so-called “Ewe Problem – that is to say Ewes, who hitherto saw themselves as a “nation state”, were politically divided into two administrative camps with different official languages. The movement for Ewe unification in southern Togoland was particularly inspired along socio-economic, social-political, and cultural factors. The so-called “Ewe problem” bedevilled the UN for a decade from 1946 to 1956 and was concerned with the objectives of nationalists who wanted not just “national home, but a homeland-state, with a flag, a leader, a national anthem, a capital, embassies abroad, representation at the United Nations, and an independent voice at Pan-African meetings” (Austin 1963: p141-142). Interestingly, the records show that “there was no Ewe state in precolonial times, although there were several semi-autonomous Ewes-peaking communities along the coast and in the Togo hills.”[6] Amenumey, however, asserts that what they wanted was “not an autonomous Ewe state but rather the grouping of the Ewe together within a larger unit of the two trust Territories and the Gold Coast’ (Amenumey 1989: p44-45). The Dagomba’s under the Northern Territories Territorial Council also supported the Ewe position that the partition had created problems for them to the extent that “the Ya Na could not exercise his full authority in Western Dagomba (Bening, 1983; p204)

3. Political Associations in Togoland (Unificationists vs Unionists)

The 1950s saw a rise in Pan-tribal movements amongst groups that had hitherto been divided by colonial boundaries. They now saw political advantage and security in being united on one side of the boundary (Prescott, 1963; p3). For example, there were constant demands by some Ewes for unification either as a separate or to join Ghana or Togo Republic.[7] Two key groups emerged Post World War II on the status of Togoland: the unificationists and the unionists. The unificationists held on to the idea of a pan-Ewe nation state encompassing both French and British Togoland whereas the unionists held on to the belief that their interests will be best served under the Crown. A popular claim of the unificationists against the unionists was that “far from being free, the Ewes will be dominated by other Gold Coast peoples if integration takes place” thus taking a similar position as the National Liberation Movement of Ashanti.[8] The proponents from the opposing camps of the debate were the Convention Peoples’ Party who were for integration with the Gold Coast (Unionists) and the Togoland Congress who were for unification of both French and English Togolands.[9]

The leader of the Togoland Congress was a man named George Antor who was a keen advocate for the unification not only of the Ewes but of both Togolands.[10] It is reported that “… a deal was made between Antor and Olympio (from French Togoland) that unification of Togoland would come first with a promise to associate in some form with the Gold Coast so that a maximum number of Ewes could come together.”[11] However, with the advent of independence in the Gold Coast, “some of the Ewe leaders including Daniel Chapman and Gerald Awumah expressed the view that the best hope for the Ewe people lay in the integration of British Togoland with the Gold Coast.”

Despite the pro-unification Togoland congress claiming to be acting on behalf of all, the historical records show that it really spoke on behalf of only the Ewes in the South – i.e. between Ho and Keta. The Africa Today report of 1957 mentions splits in the ranks of the unificationists. They noted “the Togoland Congress claims to stand for the unification of all Togoland as though this area were a natural entity. Other unificationists say let the north and center go to the Gold Coast if they wish but the south (Ewe Territory) must remain as a Trust territory so that the door may be left open for the uniting of the Ewe nation.”

4. The Plebiscite and Matters Arising

In 1954, a United Nations Visiting Team to British Togoland recommended a plebiscite to be held to decide on the wishes of the Togoland people on the issues of whether the Trust Territory should be integrated into or secede from the Gold Coast. The plebiscite came about because the British government, having granted internal self-government to the Gold Coast in 1954, informed the UN it could no longer administer British Togoland separately after the Gold Coast had achieved full independence (Bening, 1983; p205). The future of the Togoland territory was decided based on majority votes of the plebiscite from these four areas: (1) Northern Section of British Togoland, (3) Kpandu and Ho Districts; (3) Buem-Krachi District north of the southern boundary; and (4) Buem-Krachi District.[12]

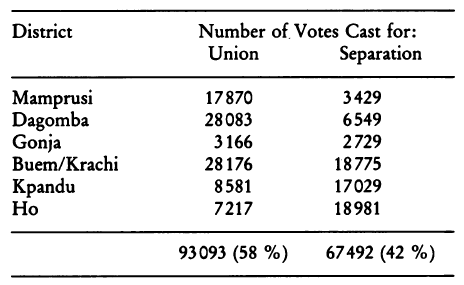

On 9 May 1956, the poll was held with an 83% voter turnout estimated at 160,587 persons. A resounding 58% of the population backed the union with the Gold Coast with the remaining 42% voting against it. The same plebiscite in French Togoland, showed a majority of the people voting in favour of the territory becoming an autonomous republic within the French Union (Prescott, 1963). Interestingly, the results showed that there was an overwhelming support for the union in the Northern Togoland region whereas the Ewe-speaking areas of the south namely in Ho and Kpando voted strongly in favour of seceding from the new Ghana. To put this into context, Ho and Kpando regions comprised only about 15% of the territory in terms of landmass.[13] On this basis, the British government therefore recommended that the Trans Volta Togoland should be integrated into the Gold Coast. This suggestion, however, did not go down well with a portion of those from the Ewe speaking regions as they had opted to join the French Togo in the plebiscite which had then attained the status of an autonomous republic. There was even an armed rebellion by the people of Alavanyo against integration with the Gold Coast.[14]

Figure 1 Results of the 1956 Plebiscite in British Togoland

Source: UN Year Book (1959) cited in Bening (1983)

Following the recommendation by the British government on the basis of the poll results, the Fourth Committee of the Eleventh Session of the General Assembly of the UN approved the union “…. and their recommendation was adopted by the General Assembly and on 6 March, 1957 the British trust territory of Togoland and the Gold Coast became the independent and unitary state of Ghana.”[15] The new Parliament of Ghana after independence adopted the UN resolution to merge and integrate the Trans-Volta Togoland with Ghana which was then given the name Volta Region.

5. Conclusions

From the above historical exposition, it is trite to say the requisite protocols were followed in the run-up to Trans-Volta Togoland becoming part of the unitary state called Ghana. It is highly fatuous for anybody to claim that they have the right to secede because the Trans-Volta Togoland-Ghana union has not been formally established by way of a unionized constitution to date. The processes adopted and the results of the plebiscite were clear: the vote was not for federal union! Rather, it was to join a new unitary state called Ghana. The Queen did not need to incorporate Western (British) Togoland into an Act establishing Ghana – i.e. the 1956 Ghana Independence Bill.[16]

This issue of secession did not start today. Indeed, some people publicly demanded secession from Ghana at a 1975 durbar attended by Gen. I.K. Acheampong at Ho. The historical records even show that a legion of Ewe chiefs also went to Lomé and petitioned the Ghana Ambassador there to initiate immediate negotiations between the two countries for a solution to the demands for the reunification of Togoland. Finally, let me restate here again that the May 1956 plebiscite duly prepared the way for British Togoland to join the Gold Coast and became a fully independent state of Ghana on 6 March 1957. The interests of elements in this fringe secessionist group should be discounted and treated with the contempt it deserves. I have not seen any 50 year expiry date on the plebiscite. Their claims are bogus!

Additional Reading

- Nugent, P., 2002.Smugglers, Secessionists, and Loyal Citizens on the Ghana-Toga Frontier. James Currey Publishers

- Amenumey, D.E.K., 1989.The Ewe Unification Movement: A Political History. Ghana Universities Press.

- McKay, V., 1956. Too slow or too fast.Foreign Affairs, 3 (2), pp. 295-310

- Amenumey, D. E. K. “The 1956 Plebiscite in Togoland under British Administration and Ewe Unification.”Africa Today 3 (1976): 126-140.

- Brown, D., 1980. Borderline politics in Ghana: The national liberation movement of western Togoland.The Journal of Modern African Studies,18(04), pp.575-609.

- Coleman, J.S., 1956. Togoland.International conciliation, (509), pp.3-91.

- Skinner, K., 2007. Reading, Writing and Rallies: The Politics of ‘Freedom’ in Southern British Togoland, 1953–1956.The Journal of African History,48(01), pp.123-147.

- Bening, R.B., 1983. The Ghana-Togo boundary, 1914-1982.Africa Spectrum, pp.191-209.

- Brown, D., 1982. Who are the tribalists? Social pluralism and political ideology in Ghana.African Affairs, 81(322), pp.37-69.

- Prescott, J.R.V., 1963. Africa’s major boundary problems.The Australian Geographer, 9(1), pp.3-12.

- Plebiscite Forthcoming in British Togoland. (1956).Africa Today, 3(2), 5-7. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4183794

- Apoh, W., 2013.Germany and Its West African Colonies:” excavations” of German Colonialism in Post-colonial Times (Vol. 49). LIT Verlag Münster.

[1] http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Group-to-declare-Volta-region-independence-on-May-9-2017-463239

[2] http://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/we-are-breaking-away-from-ghana-volta-region-group.html

[3] Prescott, 1963; p141

[4] This view is also corroborated in recent works of Adotey (2013) and Amenumey (1989)

[5] http://www.ghana.gov.gh/index.php/about-ghana/regions/volta

[6] Austin 1963: p141

[7] Prescott, 1963: p3

[8] Africa Today, 1957: p6

[9] Ibid, p7

[10] Ibid, p7

[11] Ibid, p7

[12] Bening, 1983; p205

[13] Ibid, p206

[14] Ibid, p206

[15] Ibid, p206

[16] http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1956/dec/11/ghana-independence-bill